First Ever ‘Boro Taxi’ Driver Hits Brakes as Industry Tanks

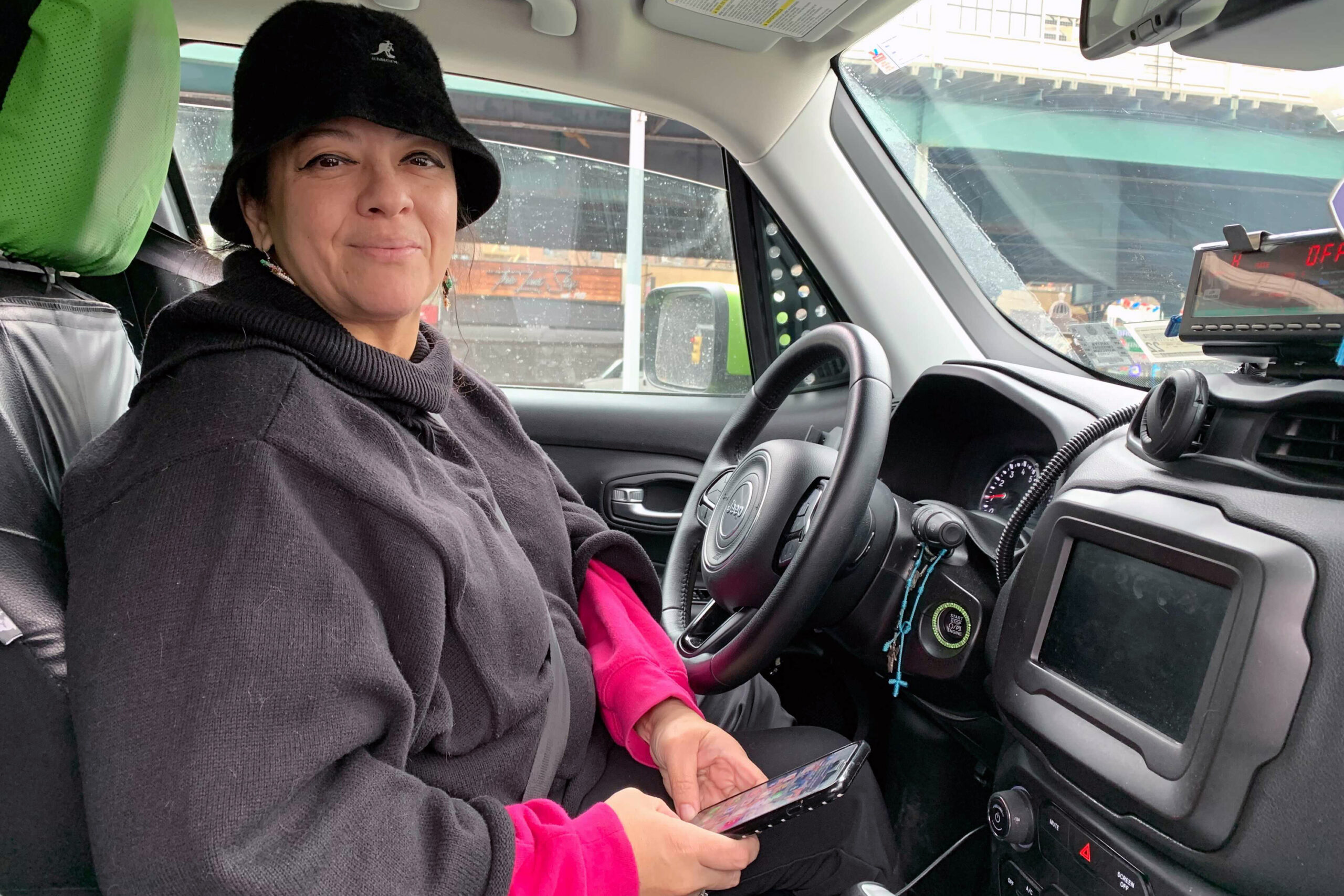

In the summer of 2013, Nancy Reynoso became the city’s first green taxi driver, proudly slapping her permit number — AA001 — on a Toyota Camry that carried her family’s dreams.

“Maybe you could retire someday or leave the car running and rent it,” she said. “That was the dream that never happened.”

Now, Reynoso has become the latest casualty in the long-running upheaval of the green and yellow taxi industry. On Wednesday she’ll turn in her Taxi and Limousine Commission license plates and the permit that allowed her to pick up street hails in the boroughs and Upper Manhattan.

“I’m throwing in my gloves, man,” she told THE CITY Tuesday. “I’m almost 51 years old and I have some hope of maybe doing something else with my life.”

“But I just don’t see anything positive coming here.”

An analysis by THE CITY of TLC data shows there were 1,162 green taxi drivers at the end of January — an 85% dropoff from the peak of May 2015, when there were 7,513 Boro Taxi drivers. And it’s down nearly 60% from the pre-pandemic tally of 2,843 in February 2020.

Among green taxis, recovery from the pandemic-driven collapse has been much slower than other forms of vehicles for hire. While ride-hailing apps such as Uber and Lyft have recovered 86% of the vehicles licensed to operate in the city, yellow taxis have recovered 58%, but green taxis only 42%, according to TLC figures.

“It’s like the greens are in the bottom of the barrel,” Reynoso told THE CITY. “Who talks about us? Nobody.”

Reynoso, a one-time livery driver, said the continued decline left her with little choice but to call it quits after nearly a decade as a vocal advocate for green taxis and after she delivered meals to senior citizens in her taxi when the pandemic hit the city in the spring of 2020.

‘We Were So Excited’

In her early days behind the wheel, Reynoso even shuttled then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg back to his Upper East Side home after the city celebrated the arrival of more than 1,000 green taxis on the road during a 2013 event at the Cine Magic Riverfront Studios in Brooklyn.

“We were totally on board, we were so excited,” she said. “We were going to be in the neighborhoods where yellow taxis don’t reach.”

Now, Reynoso has decided to take her 2020 Jeep Renegade out of taxi service less than six months after she and her husband, Wilfredo, purchased the SUV and spent close to $2,000 on a paint job and other upgrades.

It marks another blow to a shrinking sector clobbered by the rise of app-based ride-hailing services that debuted in New York more than a decade ago, but which by 2015 had flooded city streets with more than 40,000 vehicles.

“We did the first two years very well, my colleagues were making money,” Reynoso said. “But then everything went grim when the apps came in.”

The city did not put limits on the number of app-based cars, known as for-hire vehicles, until 2018, when the TLC said there were more than 80,000 on city streets.

A 2019 study by the TLC and the city Department of Transportation found that for-hire vehicles such as Uber and Lyft made up nearly 30% of all traffic in Manhattan and also contributed to average weekday traffic speeds in Midtown Manhattan dropping from 6.1 miles per hour in November 2010 to 4.3 miles per hour by November 2018.

“The city and state set up the green cab sector for failure from day one,” said Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York City Taxi Workers Alliance. “Uber and then Lyft were given carte blanche to overtake the fares.”

A TLC spokesperson did not respond to a request from THE CITY.

Desai criticized officials who pushed for the creation of green taxis and then championed the ride-hailing apps.

“It’s criminal what was done,” Desai told THE CITY.

Road Rage

The cratering of the green taxi market is in line with the broader fallout among yellow taxis. City Hall last year committed to a bailout for financially distressed medallion owners, whose debt burden was already staggering prior to the pre-pandemic collapse of the taxi industry.

But as THE CITY reported last month, hundreds of medallions have been repossessed since the deal was announced.

Reynoso said she’s grown tired of fighting for green taxis, which she said have been hurt by illegal street hails that are rarely enforced and inequality among the various sectors of the industry.

“I have to have livery insurance that, for some reason, is more expensive than the apps,” she said. “Why do you think more people are driving for the apps?”

In a tweet on Monday, she thanked taxi industry supporters, while also singling out “the politicians who all promised so much but did nothing.”

“Everybody’s suffering in the industry,” said. “And I just don’t want to be part of this any more.”

Reynoso, a mother of three who has four grandchildren, said she has begun looking for other jobs — but won’t drive for a competitor.

“I hate Uber, I hate Lyft,” she said. “The city just let them come in and flood the streets.

“How can I unite with them? I’m 100% true to my color.”

This article was originally posted on First Ever ‘Boro Taxi’ Driver Hits Brakes as Industry Tanks